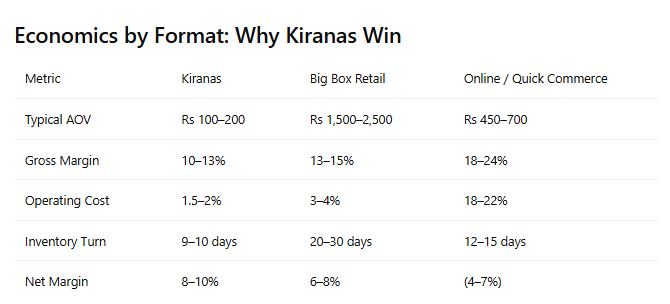

India’s grocery market is expanding rapidly, but its centre of gravity remains firmly anchored in neighbourhood kiranas. The reason is structural, not sentimental. For a majority of Indian households, grocery shopping is defined by small, frequent purchases. Average order values (AOVs) of Rs 100–200 dominate mass consumption. This single data point creates a profitability ceiling for modern trade and online models, while simultaneously reinforcing the economic superiority of kiranas.

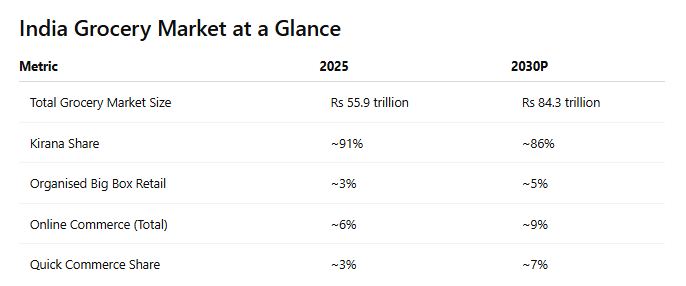

According to the Redseer report, India’s grocery market is valued at Rs 55.9 trillion in 2025 and is projected to grow to Rs 84.3 trillion by 2030. Despite the rapid growth of organised retail and digital commerce, kiranas command about 91% of the market today and are expected to retain a dominant 86% share by the end of the decade. The explanation lies in what the report terms the “AOV trap.”

The AOV Trap: A Structural Constraint

India’s largest consumer cohort transacts in grocery baskets worth Rs 100–200. These baskets are not occasional; they are repeated 10–20 times a month, driven by cash-flow realities, preference for small packs, and proximity-led convenience. While this behaviour sustains volume, it undermines the economics of scale-heavy retail formats.

Modern trade formats depend on significantly higher basket sizes to break even. Supermarkets and hypermarkets are structured around monthly or fortnightly stock-up missions with AOVs of Rs 1,500–2,500, required to absorb fixed costs such as rent, manpower, utilities, and inventory holding. When consumer behaviour fragments into low-ticket, high-frequency purchases, these economics weaken sharply.

Online grocery faces an even harsher reality. Fulfillment, last-mile delivery, customer acquisition, and technology costs make small baskets structurally loss-making. As a result, online grocery models perform best only in dense, affluent urban clusters where higher AOVs and order frequency offset costs.

Kiranas remain viable at low AOVs because their cost structures are fundamentally different. Owned or low-rent premises, family-run staffing models, negligible marketing expenses, and minimal logistics costs allow them to operate profitably where others cannot. Rapid inventory cycles, with stock turning every 9–10 days, further improve cash flow and reduce working capital stress.

Quick Commerce: Fast Growth, Narrow Applicability

Quick commerce is the fastest-growing grocery channel in India, projected to grow at 37–39% CAGR and reach about 7% market share by 2030. Within online grocery, its dominance is even clearer: quick commerce accounts for roughly 47% of online grocery today and is expected to reach about 67% by 2030.

However, this growth is not a mass-market disruption. Quick commerce primarily serves affluent, urban households where convenience outweighs price sensitivity. Its gains are largely coming from supermarkets and scheduled e-commerce rather than kiranas. As assortment depth and delivery reliability improve, quick commerce is increasingly absorbing planned grocery missions for high-income consumers, but its economics remain misaligned with Rs 100–200 baskets.

Hypermarkets vs Supermarkets: A Diverging Path

Within modern trade, hypermarkets are proving more resilient than supermarkets. Value-led bulk packs, predictable pricing, and monthly stock-up missions protect hypermarkets from quick commerce disruption. Supermarkets, which overlap heavily with convenience-led top-up missions, are the most exposed to share loss.

Hypermarkets are projected to grow at a 13–15% CAGR, while supermarkets face increasing pressure as convenience-driven consumers migrate to faster fulfilment models.

What Consolidation and Scaling Could Look Like in 2026

As low-ticket grocery baskets continue to dominate Indian consumption, consolidation and scaling in 2026 will be driven less by topline growth and more by hard unit economics. The constraint is structural: average order values of Rs 100–200 leave little margin for inefficiency. Formats that cannot profitably serve these baskets will either consolidate, retreat to niches, or exit.

In online and quick commerce, consolidation is likely to accelerate. Only platforms with dense dark-store networks, strong city-level scale, and tight fulfilment control will survive. Players operating with weak density or overlapping catchments will struggle to absorb fulfillment and customer acquisition costs on small baskets. The outcome is likely to be fewer, larger platforms focusing on affluent urban clusters, deeper private-label penetration, and deliberate basket expansion rather than mass-market reach.

Modern trade will see selective scaling, not uniform expansion. Hypermarkets with a clear value-led proposition, bulk-pack dominance, and disciplined cost structures will continue to add stores in dense urban and peri-urban markets. Supermarkets face the highest consolidation risk. Their convenience-led missions overlap directly with quick commerce, but without matching either its speed or kiranas’ cost advantage. Store rationalisation, portfolio pruning, and format recalibration are likely in 2026.

For kiranas, consolidation will not mean disappearance but aggregation. Scaling will increasingly occur through networks rather than store closures. Distributor alliances, eB2B platforms, and informal buying groups will improve sourcing efficiency, credit access, and inventory planning, while preserving the kirana’s low-cost front-end. The kiranas that scale best will be those that adopt digital tools selectively to improve stock turns and cash-flow visibility without inflating operating costs.

Across formats, 2026 will reward operational sharpness over expansion-at-all-costs. Scale will matter only when it directly improves cost-to-serve in a low-AOV environment.